My website is mostly devoted to Flavin Stories. Above, you’ll see a number of menu options, such as Real News, Social Commentary, Academic, etc.

1,978 words, 10 minutes read time.

I’ve spent my 20-year high school teaching career with a single-word classroom rule: respect. I don’t need to go over the rules one by one, I tell them, “Because you already know them. You already know that it’s not polite to hold a loud conversation while others are trying to concentrate. You already know insulting people is not acceptable. You already know to stand up and throw wrappers into a garbage can instead of making me pick it up off the floor.” I tell students that every conflict can be resolved if we always respect each other.

Even for Dylan, who in 2007 sat at the front of the class and abruptly ended a dispute by bursting out, “Suck a big one, Mr. Flavin!” He didn’t hold back at all.

The room went silent and still, and of course the other kids were eager for my reaction as all of their heads turned from Dylan to me. That kind of talk to a teacher was extremely uncommon at this nice, average-sized, rural school in Molalla, Oregon. I’m willing to bet, while they’ve all seen a few things in school, they hadn’t seen that. I guess he was pretty upset.

Despite being bright and eager for success, Dylan, a junior at the time, didn’t view himself as an academic. He was 2-3 inches taller than me, a wrestler with a ton of energy, and he had braces to punctuate his adolescent face.

That was my 3rd year (of 11) at Molalla. Dylan’s demonstration was so far over-the-top, I had a sort of instant and antithetical reaction. Having driven a city bus in Seattle for nine years prior to teaching, his outburst hardly felt like a threat. It was as if I were watching the situation from a camera in the corner of the room, or in a dream. After a brief pause, I said softly, “Seriously?”

The ensuing silence swallowed him up and forced a barely perceptible, reluctant smile, then immediately kept his dignity by digging his heels back into his argument, venting in a much more productive way. I listened, and then he apologized, knowing he had overreacted.

He was a good kid. We settled it then and there, and that was the last time he and I had that level of conflict.

My one-word rule allowed us to forge a positive relationship, as it tends to ameliorate nearly any conflict — so long as I stick to it.

In Baltimore, 11 years later, I didn’t stick to it.

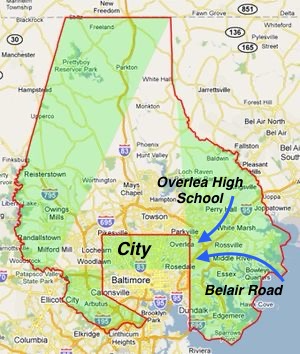

I taught sophomores and juniors at Overlea, a high school situated right at the city line, and importantly, on the Baltimore County side of that line. Unlike any other big city I’ve visited or lived, Baltimore City doesn’t share space with a county. The City is shaped roughly like the state of Nevada, but Baltimore County is massive and wraps around three sides of it, resembling a large wrist and hand reaching down from Pennsylvania.

Baltimore City has abysmal roads with tire grooves from years of neglect that are so deep you would trip over them if you didn’t watch your step. In the County, the roads are pristinely maintained.

If you drive on Belair Road southbound from the County to center of the City, the evidence of white flight and redlining are as plain as day. It reminds me of the 1984 film by John Sayles, Brother From Another Planet, where the mute, black main character, Brother, is engaged by a white earthling on the subway. The white guy shows him an elaborate card trick, and before deboarding, he says, “I have another magic trick for ya. You wanna see me make all the white people disappear?” The train, heading downtown, stops as the announcer calls out “125th Street Stop.” The doors swoosh open, the white people deboard and people of color board. Before stepping out the door, the white earthling says, “See? What’d I tell ya?” If you headed toward the City on Belair Road, the forests and parks become fewer and fewer, and the thriving businesses and homes are increasingly boarded up. The alleys become less traversable, and trash begins to litter the streets. Like the Brother, you would see the mostly white people turn almost entirely black and brown

Overlea High School is a mix of white kids whose parents have lived in the County for generations, black kids who already live in the County, and black kids whose mothers (and sometimes fathers) recently moved out of the City and into the County. At the time, it was about 70% black, 15% other people of color, and 15% white.

It was the first time I had experienced white people in the minority, and the result was that the few white kids were mostly subdued and withdrawn. The boys, especially. What a difference that made compared to the 90% white population I taught in Oregon. There were very few overt racist acts at Molalla High School because the kids are more socially motivated by obedience, and since bigotry of any kind would stand out so much, even those who had racist upbringings, of which there were plenty, they didn’t dare make a scene. The other 10% were mostly Hispanic, and there were no more than two or three black kids out of the 750 at the school, and sometimes just one.

At Overlea, being at the City line, students appeared and disappeared and sometimes reappeared to and from their desks all year because Overlea was and still is a transitory stop for parents of Baltimore City Public Schools relocating to the County for what they hope would be a better, and safer, education; meanwhile, other families regularly moved away from Overlea and further into the County, also in search of America’s promise.

It was my first year there, 12th overall. I was in the hallway conferencing with another student about her attendance, and when I came back in, Deon was entertaining in the middle of the classroom, looking at his phone and describing to the other students a meme about female genitalia. Everyone laughed, as I entered just in time for the punchline — and the most descriptive part.

“What the hell are you doing, Deon? Are you serious? You can NOT talk like that!”

“Aww, c’mon Mr. Flavin,” he replied, minimizing, grinning. “They’ve heard a lot worse, believe me.”

He was right of course, with the Internet and social media being what they are, and yet the sight of his half-mouth grin made its way under my skin. I had that feeling you might get before you do or say something you know you shouldn’t.

As Deon wandered toward the front of the room, which was not the same direction as his desk, I grabbed him at the elbow as if to redirect him to the door so we could have a talk. This is a line that teachers are not to cross, ever, except for safety reasons. Brows deeply furrowed, in a small sort of shock or surprise, he fiercely twitched his arm out of my grip, which reminded me of his athleticism (all-league linebacker and wrestler). I let go and was about to tell him to leave, but Deon walked out on his own volition, cursing under his breath.

I was wrong. I broke my own simple rule, a golden rule; I disrespected a student.

Distraught, I turned to the rest of the class and gave them something to do on their own. Or maybe I didn’t say anything. They stayed quiet, though, sensitive to the situation.

I went to the door to see if Deon was hanging around. I saw him down the hall about three classrooms down, venting to his football coach (also a teacher), who I welcomed as a go-between as I joined their spontaneous hallway meeting.

The coach supported me as well as he could, but Deon wasn’t having it; he was not going to apologize or even look at me. He repeated, speaking only to his coach, “He grabbed my arm! Mr. Flavin grabbed my arm!” With nothing resolved, the coach took him into his room, and I didn’t see him back for a week.

When he returned, I tried to talk to him, but he was shut down.

A few weeks later, while trying to motivate the class to keep working hard so they could graduate (a fairly regular conversation), I weaved in my “respect as the class rule” bit and openly acknowledged my mistake with Deon a month before. I said, and I’m paraphrasing, “Even though Deon was totally inappropriate, I was wrong for grabbing his arm, and I’m sorry for that.”

For a brief moment, Deon and I were tethered by eye contact, which, like Dylan 11 years before, evoked a barely noticeable grin from him. From that point forward, he and I were good. He had forgiven me.

I had openly respected Deon, affirming his dignity in front of his peers, and he accepted it. I had no clue at the time, but pride in Baltimore runs extraordinarily deep. I made the mistake; therefore, I was obligated to surrender. It made no difference that I was the teacher and he the student.

Another month later, overcoming limited interaction, it was finally behind us.

Respect is universal because it encompasses every golden rule, religious or otherwise. My students come from everywhere, both in Molalla and Baltimore. I can’t possibly know where their shoes have been, so the one-word rule unites us. We all get it.

And yet, I’ve long suspected that there must be something deeper than abiding by a one-word rule. Respect seemed too simple and too easy.

Then, recently, I read the 1993 novel by Ernest J. Gaines, A Lesson Before Dying, and it consumed me.

The story is about a childlike, young black man (Jefferson) in the 1940s who finds himself in the wrong place at the wrong time. He is sentenced to death row for a murder he didn’t commit. Already poor, uneducated, and possibly intellectually limited, his own defense attorney relentlessly equates him to a hog in order to argue his innocence, claiming that he didn’t have the intellectual capacity to plan the alleged triple murder. His godmother, Miss Emma, urges a young black teacher, Mr. Wiggins, to visit Jefferson at his jail cell to help him feel like a man before being executed.

Being Black in the 1940s, Jefferson’s execution was presumed; she wanted him to die with dignity.

“Respect is a commodity we exchange through actions and words, and dignity is the spiritual gain.”

As I read the story during that particular year, 2020, my mind was heavy with the murders of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, and Breonna Taylor and so many others, as well as the subsequent protests and the Black Lives Matter movement. Gaines uses Jefferson to illustrate dignity as one of our most basic human needs.

Gaines helped me to realize that dignity was at the root of my students’ needs — whether they’re white in rural Molalla, Oregon, or Black in urban Baltimore. Dignity is that “something deeper” my students needed.

Respect is a commodity we exchange through actions and words, and dignity is the spiritual gain.

I was overwhelmed with this consciousness when I read this excerpt by the inmate Jefferson, writing in a notebook given to him by the teacher Mr. Wiggins as he begins to gain confidence:

“Im sory i cry mr wigin im sory i cry when you say you aint comin back tomoro i cry cause you been so good to me mr wigin and nobody aint never been that good to me an make me think im somebody.”

It’s not an apples-to-apples comparison, considering Jefferson lives in the 1940s, is on death row, and has zero formal education. Yet, at its center is a need for a humanity that transcends comparison: dignity is essential.

I felt this truth being at the root of my students’ needs—children!—and wept uncontrollably while holding the book open in my lap. I wept because the falsely accused Jefferson is convinced he isn’t worthy.

I wept because Jefferson is a symbol of the millions of falsely accused Black Americans during the 1940s, when Gaines’s story takes place. Of the last 400 American years, and with increasing visibility, today, in 2025.

Still.

Jefferson isn’t just a literary symbol for unknown numbers of unknown people, but Jefferson is my student. All at once, he became both the abstract dread about the fictional and nonfictional past and the concrete reality of real flesh and blood people in the present.

Today.

I saw Michael, Khalil, and Taniya asking questions, writing paragraphs, trying hard. I saw Myoni’s and Kayla’s empty desks — again. I saw the smiles and the tears and hear the laughter and quarreling. I’ll always remember Kevin, not depressed today, but perpetually out of his seat. And Cameron, who could answer complex open-ended questions that no one else could while he texted a friend.

Suddenly, Jefferson is America’s Black population in the past, the 1940s, in my classroom, and inevitably, the future. Sure, I’ve always known this intellectually, but there, in that moment, an enveloping gust of tangible realness overcame my whole self with a comprehension I hadn’t previously felt.

I wept because Gaines successfully led me — a white person — to the outside of the big transparent globe that surrounds the black experience. His novel offers a close-up view of the ceaseless and pervasive truth, and I didn’t just understand it intellectually, I felt it as much as a non-black person could.

I cannot know from the outside of that globe. But, with my heart, my senses, and my words, I can glimpse, listen, and honor the dignity of the people living on the inside.

Today.

Written December 12, 2020