My website is mostly devoted to Flavin Stories. Above, you’ll see a number of menu options, such as Real News, Social Commentary, Academic, etc.

1,636 words, 9 minutes read time.

After my mom divorced my dad in 1974, she was left with $68 a month in child support for three boys (8, 9, and 12). She toggled between a decent-paying job and welfare. In that same year, my dad and two oldest siblings (Liz, 16 and Paul, 15) left the household, each for very different reasons and both out of rebellion. Paul quit high school after his freshman year to experiment with drugs and Liz quit after 10th grade to attend Slippery Rock College in Boston. She was motivated by the Equal Rights Amendment at the time, independence, and she didn’t accept the inherent expectations of co-mothering simply because she was female.

With her family cut in half, our mother mothered us with a pittance from her ex-husband and a personal income as predictable as Ford Motor Company’s bottom line. Still, I never knew we were poor.

She was a copy editor at Ford Motor Company in Dearborn, Michigan. A couple years later, after one of the times they laid her off, a woman with whom my mother had worked came to our house with a number of paper grocery bags — one for each of her boys — filled with clothing items and toys that she surmised we might like or need. She also brought several bags bulging with groceries and other basic staples for the household. I was 10, Pete was 11, and Steve was 14.

Mom called us into the dining room to meet her work friend and to reveal the contents of our bags. Earlier in the day, mom had summarily given us a heads-up about why the woman was coming, but I don’t think we knew exactly what to expect. Through subtle eye contact from my mother and sensitive language about our financial situation by her coworker, it was evident this was a kind of charity; we just weren’t sure how to feel about it.

The woman would stay for a bit, have coffee and Entenmann’s Crumb Coffee Cake, and talk awhile with my mom. It was agreed that we’d accept the gifts in front of everyone, like grab-bags at a birthday party, except it wasn’t a frenzy of discovery. Instead, we each pulled out items one-by-one. White tube socks with three green stripes were at the top of my bag. Each of us got identical but differently colored sweatshirts and maybe a turtleneck. Mom must’ve told her we were interested in sports, because we each got a different college football t-shirt from states we never thought about: Tennessee, Indiana, and Alabama.

It was a little underwhelming since the woman knew nothing about us. The odds of her really nailing it were low. Plus, it felt vaguely pathetic, so I was unsure whether we should pity mom’s coworker for having bought all this stuff we didn’t really need, or if she was there to pity us.

Why should she pity us? None of us boys understood, but I’m sure my mom was the only person in that room who was expressly aware of every nuance in that moment, like the omniscient author of our lives.

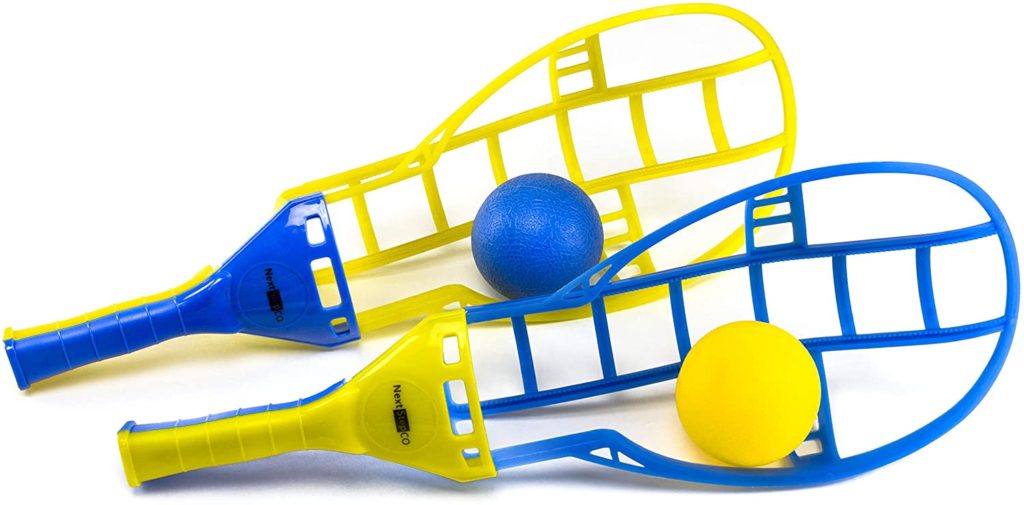

Then, Peter struck gold and pulled out a WHAM-O Trac-ball game: two blue and yellow plastic scoops with handles designed to catch a light-weight plastic ball. That was something we didn’t already have, and it looked a lot like a sport, so we showed authentic appreciation for it with real smiles, eye contact, and the body language of enthusiasm.

The work friend couldn’t have known that almost everything she bought was redundant and unnecessary. Much of what was in those bags, we already owned. Clothes, maybe a deck of cards, and some plastic things. Despite my mother’s economic plight, we never went without.

The real act began when Steve was the first to pull out tennis shoes from the bottom of his bag. Again, we caught my mom’s cues and our body language returned to rigid. My elbows stiffened, my neck refused to swivel, my view narrowed, and the pressure of the moment suddenly pinched like an unexpected improvised performance.

Pete and I paused to see what kind of shoes Steve got. All eyes were on him and his reaction, as these were clearly the big prize. We didn’t see the three stripes of Adidas. We didn’t see the trademark Puma design. No Converse star, no Nike swoosh, no recognizable brand at all. Just bargain-rate canvas tennis shoes with no design of any kind except for mustardy-colored plastic soles.

Steve held out one of the shoes, resting in both hands in front of him.

The awkward pause was interminable. We played every sport in every season, organized or not, and mom made sure her active boys had quality athletic shoes from reputable brands with soft and flexible leather, and above all — rubber soles with good traction (we called it gription).

During that pause, which I’m mostly confident the work friend didn’t fully appreciate, the same thoughts ran through mine and my brothers’ minds. Later, we conferred and agreed:

These were shoes we made fun of. We made fun of them because they looked athletic, but nothing was more disruptive to athletics than shoes with plastic soles. Non-athletes wore them, and their poor, uncoordinated bodies slipped, skidded, and stumbled on glossy gym floors as we wailed on them with the dreaded red dodgeballs.

It was a brutal time, the ‘70’s, and in the barely-supervised environs of elementary and junior high gym classes led by creepy gym teachers, we showed little mercy on the kids who wore plastic shoes. I’m not proud of it now, but that was the reality.

The intolerable notion that any one of us would wear them at all, let alone in public, was swimming among all of our minds during that critical pause. Do we laugh, like we would if this kind woman weren’t right here in front of us?

Mom’s eyes subtly reminded us: we would show gratitude. Though we knew our mother was perfectly aware that these were not shoes we’d ever wear, we pretended our appreciation, like Academy Award-winning actors, and it went something like this:

Steve: “Alright! I need tennis shoes.”

Peter, suddenly eager, reached to the bottom of his bag: “Hey, I got some, too.”

Me, on cue, pulling mine from the bottom of the bag: “Cool.”

They were identical, differently sized.

We were understated enough in our exclamation over the shoes to avoid being obvious. To this day, I am certain we pulled it off. Mom’s work friend definitely didn’t know the shoes wouldn’t get any closer to our feet than our winter hats, as our voices showed a slight increase of enthusiasm without going over-the-top.

Mom was poor, by all measures, except that she saved money. Only 40 years before the day of awkward benevolence, she was a depression-era Kentuckian for the first decade of her life. She was born in tiny Clay, Kentucky on September 1, 1929, and the Great Depression began three days later. She had one dress that she washed daily, and she made mud pies out of actual mud that she sold to passers-by for a quarter. One day, a man in a suit gave her a quarter for the one that was the most circular.

“I’ll take that one,” he said, “It’s perfect.”

Her Baptist mother shamed her for selling mud to someone, so later, out of guilt, my mother tossed the quarter down a sewer drain. Who knows what they could have done with a quarter in 1936?

For my mother, the proverbial “rainy day” was later that evening, as clear and certain as the setting of the sun. She saved and scrimped and budgeted and so, we never went without.

We had food, even if Pop-tarts were only occasionally in the cupboards and “the good cereals,” like Lucky Charms, were limited to one bowl per day. We put mayo on one slice of bread when making a sandwich; the jar would go twice as far. Save. Conserve. Be smart. Be ready.

We had clean clothes, even if I wore my socks till they turned black (the green-striped tube socks came in handy, after all). Mom made sure we had all the basics that never allowed us to wonder why we didn’t dress like other kids. We had enough food to invite a friend over for lunch or dinner. For a while in first and second grades, friends Ray Pack and Linda Kelley came over regularly for peanut butter and jelly sandwiches. We all had friends come over.

We had Rawlings or Wilson baseball gloves that broke in well, the fees for local sports programs, and yes, instead of the more financially prudent four-dollar plastic-soled shoes, she paid $20 to $40 for tennis shoes and cleats that improved our performance and heightened our confidence stepping onto the field or court.

The big-hearted woman who arrived with bags of compassion must not have been familiar enough with her suddenly unemployed coworker to know that, on welfare, mom could materialize $40 rubber-soled shoes for three boys. That she was an alchemist of selflessness who could transform poverty into deference, self-pity into wonder, and, using eye contact alone, could instruct her three sons to be grateful for gifts they didn’t need.

How could the work friend have known that her fellow copy editor at Ford Motor Company could conjure edible pies from dirt and water?

Written May 20, 2019