“More, I Want More”

Genre: Social Commentary/Humor

Product: Article(s)/blog

I’m 58 years old. Old enough to remember the introduction of Bubble Yum bubble gum, as well as the demise of the Montreal Expos. I recall when Clark bars took a child into the sugar zone as admirably as any candy on the market; then they pretty much disappeared when the same treat under a different name, Butterfinger, blitzed us with advertising. Now it’s in everything: Butterfinger ice cream, coffee flavoring, popcorn seasoning, boutique dog food—you name it. Who needs a Clark bar?

I was there in the late 70’s and early 80’s when American cars were owned by people still entrenched in the silly habit of “buying American”–even at their own expense. The business plans of American automakers, ten years behind, included the notion that they could sell poorly made, overweight cars in the face of Japanese efficiency.

I witnessed the short-lived battle between Sony’s beta tapes and VHS. The prospect was upon humanity for the first time ever: one could be elsewhere during their favorite reruns of Gilligan’s Island and never miss a minute. We thought we were being handed the power of U.S. intelligence agencies: recording video at will. So cute.

Those were the days of steroid-free baseball players, when football was just a game, basketball had dignity, and soccer was still someone else’s sport for people with no arms. And, five TV channels were all you got and you loved it, whether you loved it or not.

Ahh, the good ol’ days, when a person had plenty, and it was more than enough; enough was actually enough; and a person who had some, they thanked god they weren’t living in the Detroit or Kentucky or anywhere on the Antarctic continent.

Simple.

Back then, a stick of gum could taste good for 23 seconds, and you’d be thrilled. Clark bars had satiated people for over 70 years (since 1917). Buy an American car and your moral compass still pointed north; you may or may not get to your destination, but sooner or later someone would pick you up in their shoddy American car and you both could commiserate. And who needed videotape? A person had to really hate their lives to watch five hours of TV a day. As far as sports were concerned, people were contented to play or watch whatever was available. They were all good. Even soccer (for the most part).

For those of you under the age of 45, that’s what the good ‘ol days were like: you got something that was better than nothing and you loved it, sometimes for months at a time.

But this is a new age. It isn’t simple anymore. There’s still poverty, bigotry, corporate greed, and unnecessary war, but now our world is like one of those menus with 27 kinds of salads, 25 burgers, 19 entrees, and dessert has its own three-ring binder of choices with laminated pages covered with descriptions, exclamation points, and smiling faces.

Just make me a hot fudge sundae, will you? No nuts.

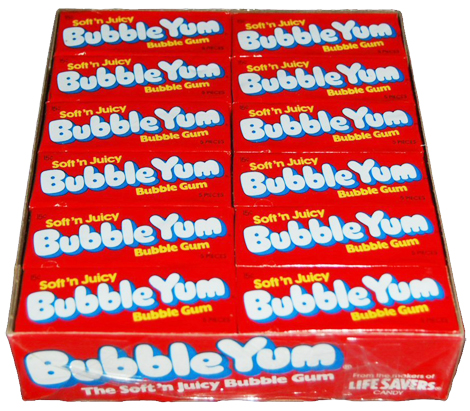

Why Bubble Yum Started It All

The change from then to now had to start somewhere, so I propose that Bubble Yum bubble gum–1975–as a moment in American history as good as any to mark the seedling of common American greed. I know what you’re thinking:

“What the hell does absurdly juicy and flavorful gum have to do with common American greed?”

Look below. You’re 12 years old. Which one do you want?

Let’s take a look at what happened when children all over the U.S. discovered Bubble Yum alongside the other options.

It was packaged better, it tasted better, and it felt better. Yes, it felt better. That is the point of departure from the simple days to now: from mediocre gum for which you’d comfortably wait till next Saturday, to a chewing product that will subdue your entire head. For smaller kids, it arrests their whole bodies. It was advertised as “soft n’ juicy”, and it was so much more. It was silky, with a mysterious texture that startled the senses. The flavor lasted longer than Dentyne, Doublemint, and Juicy Fruit combined, and you could blow bubbles the size of your face.

This prodigious gum generates a mouthful of saliva and sweet juices in under five seconds. If that sounds like an erotic experience to you, then so be it–that’s your deal. Except that, when you’re 7 or 10 or 13 years old, you savor the innocence of ecstasy. If there’s anything inappropriate about the event, it’s that in the mid-1970’s, there was nothing like Bubble Yum. Everything else was an old person’s idea of chewing gum: small, brief, inconspicuous, and probably contrived from some phony “heritage” of so-called civilized behavior, like the oversized 1977 Ford Thunderbird.

While the adults were busy recovering from the Vietnam War and President Liar, for youth, Bubble Yum was a direct protest against traditional chewing experiences: “I’m chewing gum right now. Give me a few minutes.”

The product was so desired that a rumor spread across the land: the secret ingredient was spider eggs. That’s no joke. It was so unbelievable–the Bubble Yum experience, that is–that the inclusion of spider eggs in its production was believable. It was that much of a departure from the normal 1970’s childhood existence.

By 1979, Bubble Yum, Hubba Bubba, Bubblicious, and a half-a-dozen other ridiculously awesome gum products had hit the market, and all the previous chewing choices–Bazooka, Dubble Bubble, and Bubs Daddy included–were afterthoughts. Not one of those three survived the mainstream market, and Bubs Daddy is gone altogether.

In the age of “Do what you’re told; don’t ask questions”, the new gums were a way out of the usual surrender, when kids shrugged and walked away: “What are ya gonna do?”

Bubble Yum bubble gum was a statement that said in every symbolic and literal way: the world will bend to me; The Man will make the gum I want to chew; and no one can do anything about it because we live in a free-market society hinged on individual rights.

Or, suffer through a wimpy stick of Juicy Fruit and throw it away in five minutes–because that’s plenty. Take your pick.

Common American Greed

This powerful parasitic relationship manufactured the modern American experience that the younger half of our population now takes for granted.

That marks the beginning of common American greed. We had a relationship with the makers of foods, goods, and media in which we settled for whatever was available, and then we went headlong into, “I don’t have to take it any more. I want better, I deserve better, and dog gone it, someone will give it to me.”

And they did. They do.

This gum was produced by ambitious business minds dutifully after the bottom line; advertised by innovative marketers who creatively captured the imagination; bought wholesale and sold retail by any merchant in their right mind; and it was chewed by every kid who could find a dime and a nickel in the couch or their parent’s car.

And, to be clear, I’m not suggesting that I haven’t been apart of this, or that we are somehow bad people for our modern-day wants. Like most everyone–everyone except for Jeremiah Johnson, the Amish, and homeless people–I embraced Bubble Yum and Hubba Bubba, compact discs, Pizza! Pizza!, and MTV. Today, I love a beer aisle with 450 kinds of beer, the glorious Walking Dead whenever I feel the urge, and opening Spotify to listen to almost literally any. Song. Ever.

Common American greed has come about incrementally. One new product, one new TV show, one new cable station, one new song at a time. Yesterday it didn’t exist; today it’s everywhere. The current model for free-market success in the USA was established in the late 1970’s, and now it pervades nearly everything we do. And why wouldn’t it? When marketers and advertisers realized—makers of Bubble Yum included—that they didn’t have to settle for enough, and when consumers realized that they, too, didn’t have to settle for enough, extreme measures were taken.

Enough, in the good ol’ days, was good. Now, enough isn’t enough. The definition of greed if there ever were one.

Okay, fine: it wasn’t all Bubble Yum’s fault

1975 was the year Bubble Yum took over, and by 1979, the writing was on the wall for old-school chewing products. Meanwhile, other significant events were in motion.

Five Reasons 1979 Gave Birth to Common American Greed

- President Ronald Reagan was elected and deregulated big business. Bush I and Clinton continued those policies, combining for 20 years in all. (Bush II had himself a war, er somethin’. I think. Military contract, anyone?)

- Bill Gates moved his first computer company, BASIC, to Bellevue, Washington, and the roots of Microsoft were breaking ground. This paved the way for personal computers to occupy 73% of American homes as of 2012. In 1980: that number was 0.4%. Now, 97% of Americans between the ages 18 and 49 own smartphones, almost complete market penetration.

- McDonald’s introduced the Happy Meal, 7-11 offered Big (’80) and Super Big Gulps (’81), and Taco Bell was the first of the fast food joints to provide free drink refills, transforming how America fed the poor and quenched their thirst.

- The first cable sports channel, ESPN, was launched, indicating that Americans were prepared to be sports fans upon the couch for the rest of their lives.

- Aaron Paul of Breaking Bad fame and one of the Kardashians were born.

What do political policies, the Internet, fast food, sports, an ordinary actor, and a certain trio of nobodies have in common? They each represent part of how we went from then to now, from that world of basic to our world of extremes.

The Details

Deregulation: Sell More, Make More

Politicians unleashed capitalistic potential, enabling corporate giants to say, “Thank you, Ronnie, Georges One and Two, Bill, and Barack! We’ll purchase your Capitol, re-interpret your Constitution, and spend your bailout money like spare change, and in return, we’ll purchase your next election.”

To which the politicians increasingly replied, “I can be senator for four more tenuous years!” And it was a done-deal. Except, despite the widening gap between rich and poor and record-breaking numbers on Wall Street, they’re not done. They, too, want more. (Cartoon used with permission.)

But corporate greed is not the point. That’s too obvious.

Deregulation enabled big business to make as much money as possible. Click here to see for yourself (skip to 3:15). Reagan said this at his first State of the Union Address: “In 1981, there were 23,000 fewer pages in the Federal Register–which lists new regulations–than there were in 1980.”

What were those regulations, exactly? He doesn’t offer specifics. 23,000 fewer pages in one year. Neither the Democrats nor the Republicans successfully opposed the massive removal of those pesky obstacles, and the result is simple: we’re in the midst of a Great Capitalist Experiment (trickle down economics), currently in its 44th year. The results, in broad terms, are undeniable, because, well, 44 years is plenty of time to see what happens when deregulation is roundly supported by every politician, whether s/he’s a thick-skinned, over-sized mammal (no offense to elephants) or a jackass (no offense to donkeys).

Now CEOs make well over 200 times their company’s average worker, as compared to 1979, when the ratio was 50 to 1, and had been for decades. (Note: any source will show the CEO-to-employee earnings ratio begin to explode at or around 1979.) Meanwhile, worker production in the USA also skyrocketed. As a nation, we are more productive than ever. (Again, note the sudden rise at or near 1979.) The income for millions upon millions of households or workers, on the other hand, has remained about the same for these same 44 years–it’s hardly budged. So, I suppose it’s not fair to say that deregulation has exposed greed in all Americans–just the haves who already had.

The Internet: buy more, instantly gratify me more

After decades of government removal of tax and regulatory obstacles to corporate profits, the Internet unlocked the money path. Bill Gates and Steve Jobs and the Internet, etc., enabled people to give their money to someone else in every way possible: Zelle, Venmo, PayPal, Billpay–you name it. Further, because of the new and unlimited access to information, the stretch of advertising exposure has never been more prolific. Public institutions, such as schools, are the last frontier for advertising. They are the only places that businesses can’t blanket the walls (like cheap convenience stores) with the names of their products. Thanks to the Internet, you see it, you want it, you buy it now.

Because we live in the digital age, they don’t have to advertise in public schools; it’s already in every kid’s pocket, purse or backpack. They’re getting ’em early and often.

* *

What was society like when Father Time wasn’t in every kid’s pocket, when locating his or her whereabouts wasn’t a text message away, and when insisting upon instant gratification meant you were unanimously considered to be a spoiled brat?

These devices–smartphones, tablets, laptops, etc.–have created a peculiar sense of entitlement that rarely existed in the good ol’ days. Really, if at all. This sense of entitlement (not the same thing, at all, as Republicans fuming against people who utilize government resources), is one of the mysterious, and now predictable, consequences of the digital age.

People act as if the human population has forever been provided with small rectangular contraptions that display millions of high-definition movies and entertaining video clips 24/7. You’re old if it doesn’t provide access to a library of music that the Library of Congress wouldn’t envy, or offer dozens of video games and apps.

Few people fully grasp that these devices can access every scrap of information humankind has ever compiled; in 1979, that alone was strictly science fiction.

They enable anyone to pursue an education in any subject for free. Who needs school? A few people seem to be aware that you can build an entire ancestral tree dating back to the accidental Christopher Columbus Assault of 1492, as well as instantly view “how-to” videos on everything from making meth to hunting wart hogs.

Search “how-to“ in Google. What comes up first? “How-to do anything”.

As if.

And how much does all of this cost? $30,000? $25,000? Your baby’s right arm?

It’s free, if you’re a kid. And $100 a month, give or take, if you’re not. And did I mention that these rectangles allow you to make phone calls while waltzing along any sidewalk or upon any balcony? You can text message or email anyone on the planet, or determine your exact position on the globe. While Galileo was trying to persuade a world of backward-minded idiots how the universe was constructed, you can track every star in the sky as you make bank transactions, purchase a cup of coffee or read a book. Some will change your kid’s diaper for you–if you have the app.

All of these individual attributes, and a whole lot more, are available in one slightly thick rectangle for sometimes nothing in cost.

And truly, if children had any inkling whatsoever the power they possess with respect to 99.99% of people throughout history, who had almost zero access to information, they would be licking the boots of their generous parents for supplying them with one–not running to their rooms crying because it got taken away. And people would never apologize for them, as they do all across the country: “That’s teens for you! Crazy kids.”

Bullshit.

Only 25 years ago, this kind of power in one person’s pocket was, at best, Spock’s wet dream. Even the creators of Spock’s wet dreams never dreamed that up.

Fast food & soda pop: eat, drink, and buy bigger pants

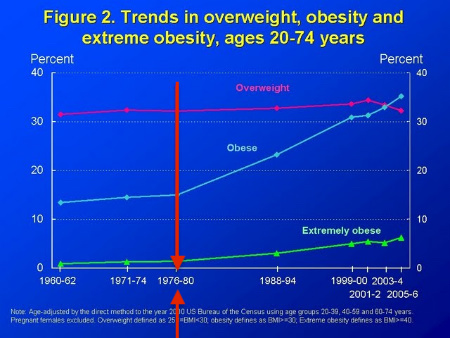

Happy Meals (’79), Big Gulps (’80), and the Taco Bell free refills trend (’79) turned ordinary. Take a peek at when obesity increased and kept right on going:

No big surprise there.

The “Happy Meal”: if God blesses America, this is all the proof we need. I was a little old to be giddy for its introduction, but Ronald’s gift to mankind had a luster that was obviously two steps up from what fast food previously offered: nasty food in a small, nasty building. Imagine the same so-called food without the toys, the colors, the smiling faces, the streamlined logos, and without all the filth that used to visibly cake the bathrooms, lobbies, and under the customer sides of the counters. It’s really not so happy without the polish.

Back then, all the filth was there, but at some point, the fast food industry asked a simple question: Do people want to eat junk food in a repugnant building, or do they want to eat fun food in a happy restaurant?

When the “Happy Meal” came out, it was more than just a good idea, it marked the beginning of a new kind of thinking for the industry: just because we sell garbage, doesn’t mean we have to LOOK like we do. That may seem obvious to us now, because that’s all we know.

The “Happy Meal” represents the same change as Bubble Yum: it, not surprisingly, allowed the 1980’s to produce the fastest-paced growth the industry has seen–before or since. According to the USDA, “In 1970, money spent on foods eaten away from home accounted for 25% of total food spending; by 1999 it had reached a record 47% of total food spending.” And in 2015, for the first time ever, Americans spent more money eating out than they did at grocery stores.

Peek again at that American obesity graph. It keeps making sense.

Free refills in fast food restaurants? I was there for that. Previously, we didn’t buy a second pop (I’m from Michigan) in our family because it cost money. We had to pay for it.

At 13, I distinctly remember walking into Taco Bell and the pimply-faced cashier (as if I weren’t the pimply-faced customer) said to me as I ordered two bean burritos with no onions and a pop: “Refills are free.” I was an eighth-grader then. I thought, WTF. Except no one said that then, so I just smiled in disbelief, looked around for the Candid Camera cameras, and filled my first cup. I didn’t actually want the second cup, but you damn well better believe I drank one or two more. I half-expected them to chase me out the door for filling up before I left the building. They didn’t, though; it really was free.

I must repeat: by no means am I saying there’s anything immoral about all of this. That isn’t the point here either. It is a simple matter of these events having changed the landscape of expectations. While the 1970’s were an economically bountiful time for Americans, no one expected their children’s meal to be cheerful, their soda pop to come in a bucket, or that anything–and I mean anything–be free.

Simple laws of competition forced every fast food restaurant to provide something visibly joyful, as well as free pop, and inside of a year’s time, every American consumed way more sugar and junk food than they actually wanted.

7-11 must have felt anxious about this counterintuitive giveaway, because they soon introduced their 32 oz Big Gulp, and then a year later that became their small size: the 44 oz. Super Big Gulp was introduced. Then came the 64 oz. Double Big Gulp, which filled up American bellies across the land.

Before long, fast food companies bumped the price from 75¢ to $1.25, but no one complained because they were still getting that second one free–and that’s all that matters. You paid AND you get something for free; it was a truly guilt-free pleasure. Just like the boy and his Bubble Yum, the girl and her soda pop got exactly what she wanted, and over the course of a hundred-thousand restaurants across the country, day after day after day, year after year, the mathematics of fast-food executives bulls-eyed the bottom line. And corporate-consumer symbiosis expanded it’s pretty head. Again.

Everyone gets what they want: more soda, more sugar, more fast food, more profit, more obesity.

It’s not a secret.

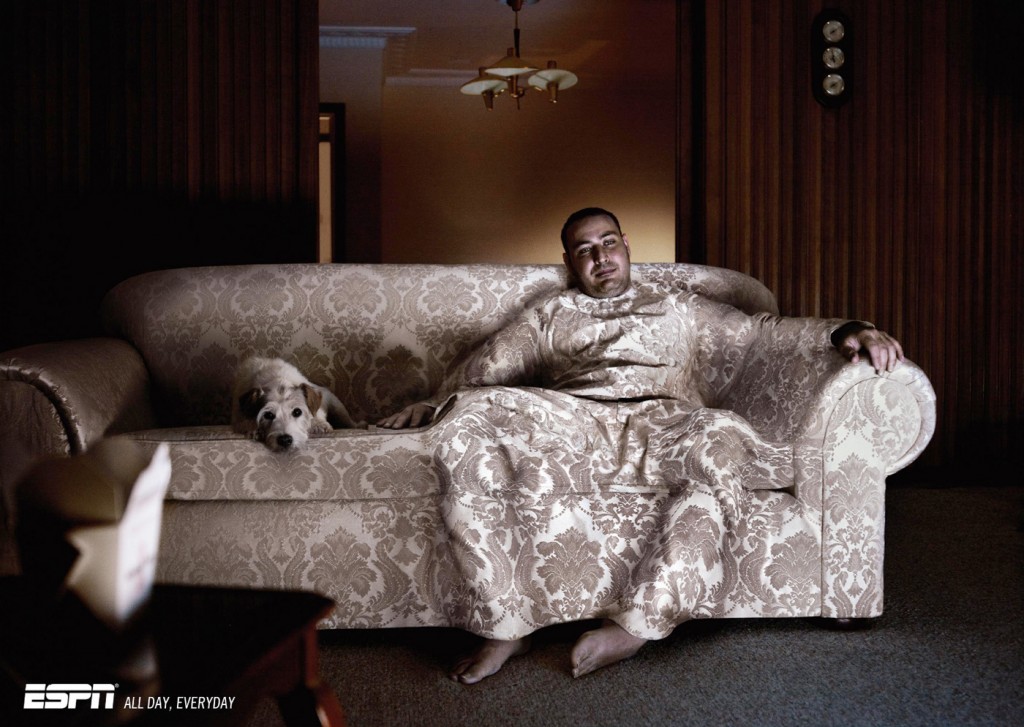

ESPN: Entertainment and Sports Programming Network

I’m pretty sure that Bill Rasmussen, founder of the network, tossed four words together so the abbreviation had a nice ring to it.

ESPN.

It sounds nice, doesn’t it?

All television nurtures future consumers, but the outbreak of televised sports in the U.S. is perhaps the most apparent cause and symptom of Common American Greed.

Remember our working definition: enough is not enough.

During the 70’s, sports was limited to Monday Night Baseball and Football and a couple Saturday or Sunday afternoon games. That means two to six contests a week, or 8-20 hours out of the 168 that make up a 7-day period. After work or caring for a family all day, upkeep of a house or apartment, fixing a meal or two, spending some heavily presumed quality time with the family, and other hobbies or personal interests, 8-20 hours of televised sports each week was plenty–even for the avid sports fan.

Now this: 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, multiple networks.

Let’s math this out: we went from 400 to 700 hours of televised sports each year in the 1970’s–depending on whether the Olympics were on or your local team made the playoffs–compared to… wait for it…

8,760 hours on their flagship station, ESPN, alone. In a single year. As calculated by multiplying 24 hours by 365 days.

Don’t vomit yet, there’s more. Another 8,760 hours for ESPN2. And another for ESPN3, 4, 5, 6, and 7, as well as ABC, ESPN Classic, ESPN International, ESPN Radio, and their latest addition to the Disney family, ESPN: Inside the Colons of Athletes.

24 x 7 x 365 x 10+ stations = you figure it out.

I read in the Wall Street Journal that Disney, 80% owner of the sports channels, is lobbying politicians to have days added to the calendar. They contend that 380 days would help their bottom line. Bob Iger, Disney’s CEO, said, “We have the right to do business without government regulation on the calendar, which belongs to everyone, I might add. Fifteen extra days is all we ask.”

While a 4% increase in calendar days may seem like a modest request, there’s no fairy tale ending to this story, because NASA explained that we cannot tamper with the earth’s revolution around the sun; the company will have to settle for televising only about 50,000 hours of sports each year.

Unfortunately, it gets worse for the mega-media gigantosaurus. They have competition: TBS, TNT, FOX, CBS, NBC, CBC, and another FOX channel or two.

Tens of thousands of hours of sports, all selling advertising to millions of people who a few years ago were doing anything but watching ESPN. The were having lunch and digging Buddha, sitting alone on a city bench, getting drunk and sentimental at family Christmas parties, and possibly even walking out the door to actually play a sport. (Photo below by John C Flavin)

24 x 7 x 365 x 10+ stations.

Then there’s the other 480 channels or so that are non-sports channels. Many of them are good, most of them are not, but in short, TV went from 5 fuzzy channels in the 70’s to 500 or so options, with a variety that boggles the mind. The advertising pounds home the need to buy more pop, fast food, bigger pants, diet pills, cars, diluted beer, new televisions, television shows, movies, computers, smartphones, GPS, and skin moisturizer. Everything.

Everything gets tens of thousands of hours of increased exposure to encourage only one possible thing: break out your wallet and transfer your money to someone else. Buy it now. Consume.

All things considered, it’s a miracle we don’t have a 75% obesity rate. In fact, it could be argued that our show of restraint has been herculean.

More, I want more. We don’t just think it, it’s who we are.

Non-sports television: extreme and distract me

Let’s face it, zombies are getting kinda cute. When we watch Warm Bodies or Zombieland, laughter and fascination take over, and without notice, the living dead are no longer horrifying biological paradoxes, they are delightful–like Happy Meals, free pop refills, Bubble Yum, and deregulation. We expect a lot of zombies who plainly devour the neck tendons of this character or that; otherwise, it’s routine drama.

One could argue that The Walking Dead was once the most extreme television show. Unfortunately, after a couple seasons, the fear of an actual zombie attack had become secondary to the fear of regular living characters, like Negan, who is sociopathic and ruthless. Regular living characters who are sociopathic and ruthless, though, are a dime-a-dozen these days. Sorry, Negan.

This is why The Walking Dead is not the most extreme show on television: the display of living dead people who eat living live people, who are later reborn only to eat their mother or father, is not the most horrifying part. Negan is. When zombies become your second-worst fear in a show about zombies, the producers aren’t doing their job. Or maybe their viewers just perpetually want more.

The excess of modern television is also evident in Breaking Bad. What was it about?

Walt, a tired and ordinary high school chemistry teacher, is diagnosed with cancer. In order to care for his family following his likely death, he produces and deals “pure” blue meth with his former student, sales associate, Jesse Pinkman. Together, they combat the Western Hemisphere’s biggest and baddest drug pushers and defeat every last one of them while outsmarting all levels of law enforcement. Meantime, his cancer goes into remission.

An unexceptional teacher and some loser kid: international cartel victors. Does it get any more extreme than that?

I asked several 20-somethings which modern-day show they thought was most radical, and they agree that Walt and Jesse take a back seat. They quickly dismiss The Walking Dead as cliché, and True Detectives gets honorable-mention. Consensus quickly lands on either Sons of Anarchy or Game of Thrones, then Anarchy wins out because it “could happen in the next town over.”

“Brutal,” Matt said.

But it doesn’t matter which one is most, or whether or not they are gratuitous: everything on television is more extreme than ever, no matter what your point-of-view may be.

What makes Aaron Paul’s character, Jesse, a symbol of extreme modern television is his relative mediocrity. His character, which is despicable on so many levels, gets lost in the ocean of competing entertainment. He is a lethal-drug-selling, simplistic loser who gets a glimmer of morals sprinkled into his personality only because his circumstances overcome his feeble intelligence. His character is the epitome of extreme inasmuch as he is nothing, and yet he sits atop so many dollars and so much success at the cost of so many people’s lives.

Episode after episode, he keeps coming back, and we keep coming back, and he keeps selling meth, or killing people he doesn’t want to kill, or doing something stupid.

(GIF Credit: Unknown)We viewers get what we want–improbable yet sufficiently believable (spider eggs, anyone?)–and still it is inadequate, average, pretty good, crazy. We get what we ask for when zombies chomp neck tendons or Jesse throws millions of dollars around poor neighborhoods or Walt allows Jesse’s girlfriend to die slowly right in front of him.

Radical, but not enough.

What is shocking is that, to bright young 20-somethings, it does not matter that Walt was once an upstanding public servant, and then he sold the icy blue blood of Satan to thousands of vulnerable Americans, killing everyone in his path. That is now the harbinger for, “Yeah, that’s some crazy shit, but if you really want to get radical, watch Sons of Anarchy or Game of Thrones.“

What is extreme is not Jesse himself; rather, that the extremeness of his character hardly gets noticed. In fact, to many, he’s lovable.

Brutal.

Andy Greenwald writes on grantland.com:

“My primary concern these days is for my fellow adults. Television, particularly the high-minded prime-time television I often write about, is awash in death…and on HBO’s prestige dramas, blood burbles and sprays like water in the Trevi Fountain. Some of this carnage is artistic and some of it is gratuitous, but eventually all of it takes a toll.”

(Photo of Trevi Fountain by Stevenfruitsmaak, commons.wikimedia.org)

What does that so-called toll look like? Is there a consequence to perpetually watching television today that is more extreme than television last month? We’re long past Breaking Bad. We’re going to need more. Much more.

We viewers have moved incrementally toward increasingly twisted plot lines, characterization, and violence. But why?

Distraction and profit. That’s why. It’s that symbiosis thing. We, the public, need distraction, and they, the entertainment suppliers, need profit. Their drive for profit dictates the need to move toward more extreme so we don’t get bored.

Our appetite for entertainment is not an accident. Life is hard. Internet and television distractions are like medication, and that kind of medication is profitable. This is no more a secret than explaining America’s obesity epidemic.

Nicholas Carr, who wrote the book, The Shallows: What the Internet is Doing to Our Brains, has this to say about Google:

“Google’s profits are tied directly to the velocity of people’s information intake. The faster we surf across the surface of the Web–the more links we click and pages we view–the more opportunities Google gains to collect information about us and to feed us advertisements…The last thing the company wants is to encourage leisurely reading or slow, concentrated thought. Google is, quite literally, in the business of distraction.”

Television is on steroids compared to 1979, the Internet is a “super highway” that creates a virtual conduit of information from their strategy rooms to our brains, and both deliver a constant flow of advertisements. All day, everyday (thanks, ESPN).

This pursuit is not new. Carr cites Frederick Winslow Taylor from the 19th century as being a catalyst for businesses to seek “maximum speed, maximum efficiency, and maximum output.” Think Henry Ford’s famed assembly line.

In other words, America’s free market is functioning exactly as “Taylorism” theorized (not including maximum worker wages, of course):

- CEO pay & company profits are through the roof

- Worker production highest ever

- All information available to all people

- More food, pop, drug prescriptions

- Hundreds of thousands of television hours

- God knows how many Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and pornography hours, but one thing we can be sure of: there’s more than ever, and there is no indication they will slow.

Then there’s reality television. It is so common that three nobodies have netted millions of dollars for doing nothing. Americans have an endless tolerance, it seems, for viewing material that produces nothing, amounts to nothing, relates to nothing, and means nothing. And yet, what do we get?)

We even clamber for more of nothing.

So what, now what? From Bubble Yum to Infinity

The introduction of Bubble Yum bubble gum is symbolic of modern-day America, in which our unique brand of common, everyday greed amounts to a colossal first-world problem. The need for more is inherent in a free-market society, and, at least as far as Americans are concerned, our so-called problems pale in comparison.

Some might argue:

- When the world has countries like North Korea, led by a tyrant straight out of Dark Horse Comics, who cares whether kids chew awesome or crappy gum?

- When we witness the continually war-torn Afghanistan and their 90% illiteracy rates, who cares about iPhone-toting kids running around every town huffing and puffing about their insensitive parents?

- When desperate Sudanese men swing machetes like pillows in a pillow-fight, who cares how much Andy Nelson and 80 million other guys sit in their sweatpants watching race cars go round and round an oval track on ESPN?

- When former President Trump is openly guiding an insurrection against our nation, what difference does it make what’s on TV?

- Everything about common American greed is rooted in our free right to choose, just like the Founding Fathers intended.

We sit comfortably in our immortal national lounge chair of consumer power, wallets at the ready, watching what we want, eating everything x 3, and digitally ordering all of our desires and whims despite the inconvenience of knowing our plastic cards may expire this month.

In short, we got it good. So what’s wrong with wanting more and getting what we want?

Tim Wu, professor at Columbia Law School and the author of “The Master Switch“, has this to say about the impact of modern technology: “Make no mistake: we are now different creatures than we once were, evolving technologically rather than biologically, in directions we must hope are for the best.”

Translation: we are amidst two enormously influential social experiments. Not only are we in the middle of the Great Capitalist Experiment, as mentioned above, but because technology has advanced so fast, according to Wu, literally no one knows how the Great Technological Experiment will turn out.

In 2014, Major General Allen Batschelet, the man responsible for U.S. Army recruiting, says this about youth in America:

“Today, about 15 percent [of possible recruits] are disqualified for obesity,” says Batschelet, “and we think by 2020 that number could go to 50 percent. About 70 percent of Americans ages 17 to 24 are not qualified to join the Army. The factors that we use to measure and evaluate people to join the Army, increasingly [are] not able to meet those requirements, and it’s very troubling…”

Translation: the United States military has determined that there is no end in sight for America’s pursuit of more, and it won’t be just the southern states and Michigan that will be dark red, as seen in the GIF file below which show the growth of obesity in America from 1985 to 2010.

(Nauseating, isn’t it? A few light blue states in 1985. Think of how much lighter we were in the 1970’s. GIF found at slate.com)Noam Chomsky has this to say about America: “Neoliberal democracy. Instead of citizens, it produces consumers.”

Translation: we are buyers, not voters. We’re target populations, not participants. We’re tools, cogs, sheep, and we are neurotic dogs contained in a back yard continually waiting for products that are extreme, because new isn’t good enough. We’re seeking maximum because better isn’t better anymore. And we search for ultimate because so-called improved has lost all meaning.

Enough is not enough.

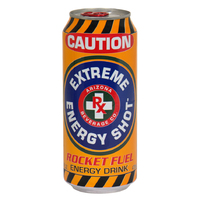

I first caught wind of this smelly practice to present every product as being more than it actually is while shopping for milk.

There it was in the dairy section of the supermarket: “Extreme Milk.”

I was already accustomed to extreme juice, extreme Mountain Dew (which is called Code Red, representing extreme danger…because, you know, it’s soda), extreme detergent, extreme acne medication, extreme this, extreme that.

Energy drinks have replaced ordinary soda because ordinary carbonated drinks with ordinary names, such as Dr. Pepper or 7-Up, won’t cut it.

But what will makers of energy drinks do to one-up themselves when rocket fuel is no longer extreme enough? (Photo credit) When “Monsters” and “Nuclear” and “Total Freakin’ Insanity” for names of beverages is all tired out, like someone else’s sleepy grandmother?

What will they call it then?

When I saw that milk was also labeled “extreme,” I had to see why. It was milk, after all, so there had to be something that stretched the boundaries of your average dairy-ingesting experience.

Nothing. The usual 25% daily value of vitamin D, 30% DV of calcium, and some protein. Upon further inspection, the label offered nothing more than the blighted hope of marketers to somehow, anyhow, by all means necessary, make milk more than milk. Because milk was not enough.

What’s wrong with wanting more and getting it? Too many people can’t think beyond the immediate and obvious logic of the question? And I do mean, they cannot imagine consequences beyond a few weeks. For them, the opposite is true: wanting more and getting it is precisely their definition of living a free and independent existence. Common American Greed is, to some, a common American right, which is why thinking beyond a few weeks is totally unnecessary:

Everything is good; I got what I want. What else is there?

It doesn’t answer a lot of questions about the changes from the 1970’s analog America in which I grew up just north of Detroit’s Eight Mile Road. Racism, sexism, and homophobia didn’t disappear because Bubble Yum was superior.

The power to record I Love Lucy willy nilly does nothing to eliminate poverty; according to Time magazine, “The poor in the U.S. are significantly worse off than their counterparts in Europe and Canada—a total reversal from 35 years ago.”

35 years ago at the time of that article, incidentally, was 1980.

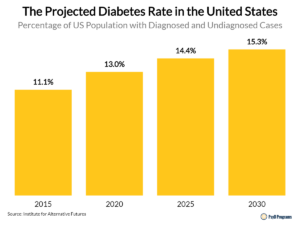

Speaking of 1980, free soda refills and supersized fast food in the digital 21st-century doesn’t help our monthly budgets because any money saved at Taco Bell is lost addressing correlating health problems. For example:

The ability to watch anything at all–from violence on Youtube, to nothing at all on regular TV, to sports 24/7/365 x 10+–does nothing to prevent America’s decades-long wars, the trillions of taxpayer dollars spent, and the tens of thousands of soldiers coming home dead, permanently disfigured or unable to cope and do much more than hide away in living rooms because post-traumatic stress disorder has taken away their lives–at further expense of American taxpayers.

And for what? More. Energy. Choices. Freedom.

Politicians didn’t invade Iraq for oil; they did it so we can sustain our quality of life. Or, someone’s bottom line. Or both. Energy is the glue that binds American consumers to American business. And the government ensures that we the consumers stay permanently fastened to the need for more.

In 1980, as naturally as skin cancer forms on the foreheads of old people in Arizona, corporations capitalized on deregulation. Cable TV increased their paying customer base from 12.2 million subscribers in 1977 to 67.6 million in 1999.

Today, 78% of households pay for a television package and 115 million people watch ESPN.

It used to be free. All of it.

Meanwhile, Bill and Steve noosed up every hermit and homebody in every crevice of the world who avoided the reach of the almighty television, all of them persuading us to grow our pants sizes as a direct indicator of growing the economy. As one Chicago business executive who wishes to remain anonymous recently said, “Hey, if the national belt size increases one more time, I’m getting that yacht.” (Photo by Tina Smothers — the man in the picture is not the business executive just mentioned.)

But we didn’t just get bigger and sit on our cans watching their ads for longer: we got what we wanted. Everything we ever asked for and a whole lot more.

To be fair, the last 44 years has allowed for more choices, more productivity, and the level of innovation compared with any nation at any time in history has been inconceivable. To a large extent, because the Internet is not yet owned by large organizations, free speech in the forms of Facebook, Twitter, blogs, and one’s right to read them all has created arguably the greatest force of democracy known to humankind.

And yet, what next? We can’t add days to the calendar to sell or buy more. We can’t infinitely extract resources out of the earth. We can’t be more extreme than extreme.

We have two options if we want to continue the pursuit of more: increase the population (add consumers) and advertise more. But how will they get our attention when the very words (i.e., Rocket Fuel, Nuclear, Total Freakin’ Instanity) being used to describe what they are selling have reached a meaningful end?

Extreme means to be “at the furthest end.” Extreme milk didn’t last because, well, at some point the advertisers realized: what next? Extremer milk? If so, what comes after that? Extremest milk? Nah, sounds too much like extremist. Extremerest?

Ultimate (and ultra) means “the most extreme”. We currently have the Ultimate Fighting Championship. Here, the soft, wimpy boxing gloves come off and no one has to endure the dullness of waiting for two upright people to beat each other from a standing position, which, in all likelihood, could end with both of them still standing.

The demise of UFC is inevitable: at some point, we as a population will get bored with these routine pummelings. Sooner or later, the UFC will die on the vine like boxing did, and something more extreme will take its place.

In 2017, the iPhone 6 got “bigger than bigger”, and maybe consumers bought into that meaningless statement until they brought it home and realized that all they ever wanted or needed was this:

Enough. Something that is just the right size.

God forbid.

And if no one is happy with “bigger than bigger” because they decided–somehow–that it is not enough, how will Apple describe the next generation of iPhone? “Extreme maximum ultimate bigness, bigger than just the right size but not too big for Goldilocks”?

You can see where this is headed. Apple’s description of their newest, latest, best phone ever is the height of advertising absurdity. The epitome of America’s free market. No one, not even them, could tell you what “bigger than bigger” even means, and here’s why:

What they meant to say was: it is enough. Enough is, in fact, enough.

Booorrrrriiiing!

This matters because we have been on this ride from the meandering 1970’s world of Juicy Fruit and 5-channel black and white TV’s, when enough was plenty, to the digital grip of highly-qualified marketers, may they sell a political agenda, your child’s milk or a TV show about mutilation. What they are selling cannot go past extreme, maximum or ultimate for one simple reason:

There is no language for it.

Nothing can be described, named or otherwise sold any more severely than it is now, or has been this past decade.

How will they sell what they’re selling without the language to convince consumers that their product has further improved one more incremental step?

Unless, of course, we go to infinity, in which case: anything goes.